O Drakos (The Monster, ο Δράκος 1956 Koundouros)

Opening scene: Blind men sing New Year’s Eve carols and beg on a street while a poster is glued to a wall, which, as a distancing device, is advertising the same film that we are watching. It is glued above an advert of the director’s previous film Magiki Polis (1954). The poster resembles one inviting you to the circus. Throughout the film there will be a parade of characters and settings strange, bizarre, unsettling, and unpleasant that will both attract and appal us.

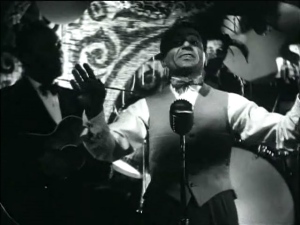

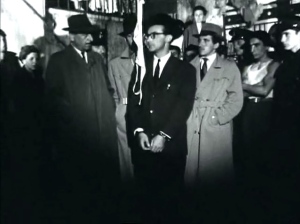

The use of the Grotesque in O Drakos is subtle. There are no Lynchian dwarves or plagued men in heavy makeup dying in Venice; there are no drag queens or hermaphrodites to escort the scared fugitive protagonist through the dark underworld that he enters. Instead, the Grotesque takes the form of a femme fatale speaking in an annoying unnatural baby voice to suit her name, Baby; it takes the form of suffocating balloons and balls in partying streets and nightclubs; a landlord’s loud family with an obviously adult daughter dressed as a child and playing with childish things; a nightmarish clinging rocking doll given as gift; an exaggerated gesturing barman, a slimy man introducing the acts, a vulgar archaeologist cleaning his ears; turntables in the middle of the street; a parade of blind men and women; kitsch tourist posters for Greece on the walls and ‘welcome to our foreign friends’ signs on top of prostitutes’ beds; overacted scenes of macho men crying and kissing violently; more balloons – animal balloons; hysterics of a whole neighbourhood at the arrest of the Monster – Drakos, while a bright white bra hangs in front of him. When he returns to the nightclub before the big heist, the mobsters are in a drunken state of preparation, they bow to him frantically, almost ironically, and each one prepares with personalised rituals of religion, homoeroticism and grooming. Other cut their wrists and become blood brothers. And the Monster – Drakos – Clerk dances a pathetic dance among all this macho underworld poverty.

Koundouros’s subtle Grotesques are not appalling. He’ll employ them again in 1922 (1978) and Bordello (1984). They become what they are out of their inner turmoil and to set the scene. They never mean any harm.

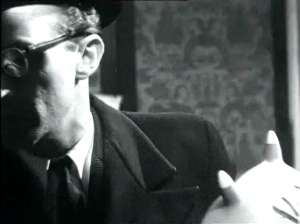

Instead, it is the prevailing shadows that are full of dread. The director and the cinematographer drown this grotesque microcosm in the darkness. Even the morning scenes seem threatening and claustrophobic. Koundouros had studied Fine Arts so it is no coincidence he chooses to use painting techniques in film. The sets are expressionistic from the very first plot scene of the Clerk inside his dark, weirdly-angled office. The lighting remains low-key; in form we have Clair-Oscur (light and shadow used to define the objects) that reaches Tenebrism (extreme contrasts of dark and light as dominant style) as far as this does not impair the realism of each shot. In the office, in the streets, in the nightclubs, the poor souls are whipped by these violent contrasts of light and darkness, and this darkness is always ominous. The lighting creates the set, sets the atmosphere and reveals the emotional troubles of the characters. In contrast though to other expressionist films, like the German expressionism of the 20’s, the reality is not distorted. Expressionism is the stylistic vehicle used so that we follow the Clerk and the characters that frame him into their angst.

The expressionist form and Chiaroscuro techniques together with the subject matter of mobsters, the underdog, femme fatales, heists and nightclubs lead to the unavoidable link of O Drakos to the Film-Noir which was at its height in the 50’s. Urban setting, the underworld, pessimism, cynicism and betrayal can all be found in this film, too. The characters are all trapped in a labyrinthine city and in the dark. They are bitter and alienated. Their morals are not clear – they are unlawful to rise out of their misery, not for the thrill of it or for riches. In the same way, the Clerk chooses to deceive, to accept the mistaken identity of the Monster-Drakos and by doing so to escape his own disheartening, his loneliness and his psyche’s bleeding.

It would be unfair though to consider O Drakos principally as a film-noir, as the connotations of ‘thriller’ would do it little justice. There is no surprise and no suspense. The fates are predefined. There are no heroes, only the Lost. Because the film’s main concern is Realism. Expressionism and Film-Noir are employed just to serve a realistic modelling of the life of all these people. In principal it is a neo-realist film. This marriage of styles was rejected by contemporary critics and the audience alike. The film was described as an ‘abomination’ even by inspired critics of the time (A Kyrou).

The intention is to show the struggle of the working class, to either find meaning (clerk) or a way out of extreme poverty (mob). Apart from the main actors, the rest are non-professionals. They are poor and they are desperate. It is to these underdogs that the writer offers the stage. There are a few outdoor scenes following the typical Italian neo-realism trend, but Koundouros has masterfully transported neo-realism from the crowded streets to a crowded nightclub, applying the same rules.

And the resolution has nothing to do with morals. Only with sadness.

O Drakos (1956): the beginning and the end of neorealist grotesque film noir.

Plot synopsis:

Based on a script by I Kampanellis (Stella (1955), the Abduction of Persephone (1956)). A timid little man, working as a clerk, finds himself alone and disillusioned on a New Year’s Eve. On his way back home and by looking at the newspapers he realises he possesses an uncanny similarity in appearance with a renowned serial killer whose photograph has just been published. The word Drakos (Monster, Dragon) is used in Greek for serial killers, serial rapists etc. He soon finds himself running away, as everyone he knows as well as the police mistake him for the Monster. He is taken in by a femme-fatale woman and lead to the nightclub in which she works. There he meets Baby, another cabaret girl who he warms up to. We soon realise that the nightclub is run by a circle of small crooks, planning a big heist involving selling antiquities to ‘the American’. The mob is run by the bar’s owner but they lack a strong Leader to inspire them before the big job. When the Clerk enters the scene, he is mistaken there, too, for the Monster. The “boss” sees in him the leader they are in need of. The Clerk does not deny that he is actually the Monster. The mob becomes delirious and hopeful. That night the Clerk-Monster is arrested while leaving the ‘hotel’ the two cabaret girls are staying in. He is humiliated by the Police that realise he is just a clerk. A crook at the police station notices the event. In the meantime, news reaches the Boss that he is not the real Monster. But he knows that enthusiasm and hope are so badly needed by the gang to succeed that he chooses to play along.

That night, the crooks prepare in delirious dances and rituals for the heist. They welcome back the Monster in a frenzy. They are all happy and hopeful because as it is revealed they are all just poor desperate trying to find a way out of poverty. The Clerk-Monster joins in their drunkenness. O Drakos is played by a famous comedian at the time, Ntinos Iliopoulos giving an amazing performance. A close-up of him, realising his fate, with his glasses removed is of the most powerful scenes of the film. Soon, the crook from the station arrives at the nightclub to reveal the truth. The news crushes the dreams of all those desperate people. The Clerk is stabbed. He leaves the nightclub stumbling but alive. Refuses the help of the Boss to take him to a hospital, he chooses to let himself die. He is found by early workers lying on the wet asphalt. The crooks watch. ‘At least this one can rest now’ murmurs the Barman.

-ulalume